Every other day, it seems, Boris Johnson changes our national energy strategy with the rapidity with which he changes his socks. On a Monday, it’s new nuclear, Tuesday it’s hydrogen, Wednesday it is onshore wind farming – and yesterday he’s dipping his unsocked foot into looking again at fracking. But on every one he then backtracks. What stays constant though is a commitment to offshore wind. After all, what’s not to like? It’s green, it is normally out of sight and out of mind and it doesn’t seem to damage the environment in any great way.

But that last claim is not, unless qualified, strictly true, at least as far as our stretch of the North Sea is concerned.

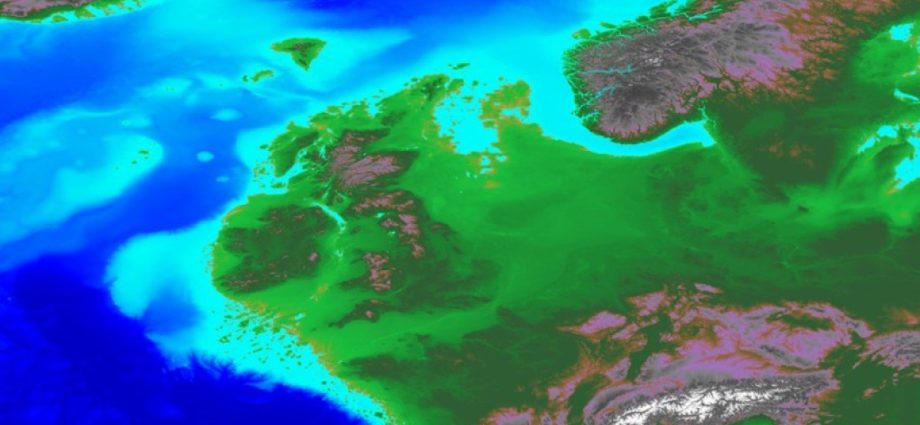

Doggerland

Let me explain. It has been long known that there was once an abundant society in what we now call ‘Doggerland’ from the time when our local forebears could lope off from what is now the beaches of Seaton Carew, Redcar, Marske and Saltburn, and, making their way through dense forest and salt marsh, carry on going until they reached higher land in today’s Schleswig Holstein or Bremerhaven.

Even here, we have skin on the bone for this. Our knowledge from low tides off Redcar and Hartlepool demonstrate even today the remains of a submerged ‘prehistoric forest’ of pine and oak, preserved in a water-logged, petrified, state. This has long been known. The ‘Redcar and Saltburn Gazette’ of September 1871 stated:

“The first written account of the submerged forest at Redcar was after it was revealed earlier this year. The main and the more expansive area is in line with West Terrace and behind, what is now a public house. When uncovered it is a vast bed of roots, stems, branches, bark and even the leaves and fruit of the many species of trees are evident. Mainly consisting of Birch, Larch, Beech and Hazel the appearance is almost like that of a peat bed and when dried, burns in a similar fashion. As well as trees, the antlers of red deer and the tusks of wild boar were found and were very well preserved.”

The idea of a “lost Atlantis” far further out under the North Sea connecting Britain by land to continental Europe had been imagined by HG Wells in the late 19th century, with evidence of human inhabitation of the forgotten world following in 1931 when the trawler ‘Colinda’, skippered by the wonderfully named Pilgrim Lockwood, dredged up a lump of peat containing a spear point.

Modern research

While the last decade has seen a growing number of scientific studies, including a recent survey of the drowned landscape by the universities of Bradford and Ghent offering further clues to the cause of its destruction, it is the work of “citizen scientists” that has produced some of the most exciting artefacts, allowing a full story now to be told, according to Dr Sasja van der Vaart-Verschoof, assistant curator of the Netherlands National Museum of Antiquities’ prehistory department. Sasja seems a fun person, looking beyond dry treatises to reconstructions of later Iron Age life along the Dutch shoreline and way out into Doggerland. She is, she says, especially obsessed about the analysis of the weave patterns and the dyestuffs found on surviving pieces of clothing fabric from subsea excavations. She calls herself, as a result, the “Overdressed Archaeologist” as she recreates the patterns and dying techniques to show what the dress from the Iron Age could be like, and as you can see she wouldn’t be all that out of place at today’s Glastonbury dressed as she is.

Sasha says of the world of Doggerland, a fertile terrain of hills and valleys, large swamps and lakes, peopled by hunter gatherers, and later, the first farmers and builders of communities, who communicated on a regular basis with people living on the Western uplands of today’s NE hinterland and who would have been the suppliers of tools and artefacts fashioned from mineral assets like the tough whinstone from the “Cleveland Dyke”, that it was

“a wonderful community of people at one with their surroundings and their environment.”

They were, after all, our immediate ancestors. Doggerland only vanished in geological terms a gnat’s blink ago around 8000 BCE. The people of that great plain were not primitive hominids – their dress alone, made from fabrics obtained from hemp and flax – shows that. They were skilled tool users capable of precise and complex multi-staged tasks. A drawing in the exhibition imagines one particular sharp tool was used as a razor by one to shave another’s head.

The lifetime of Doggerland stretched over 20,000 years – far longer than our comparatively brief spell on what is now an island. The terrain and peaty ‘black earth’ soil would also be perfect for the transition to early farming as Doggerland moved into the Iron Age, but hunting was still crucial up to the days that the plain became inundated by rising sea levels. The open grassy plains of Doggerland were an ideal grazing ground for large herds of animals such as the ancestors of today’s horses, reindeer and wild bison. By its last years, some 8,000 to 9.000 years ago, it was a society showing distinctly modern forms, based on settled farming, supplemented by fishing and wild fowling – little different to life in the Fenland districts of Roman Britain.

A warning for our future

But Doggerland is not just a curiosity of our past – it is also a warning for our own future too. Sasja said:

“Like us today, It was not some edge of the earth, or land bridge to the UK. It was really the heart of Europe. There are lessons to be learned. The story of Doggerland shows how destructive climate change can be. The climate change we see today is manmade but the effects could be just as devastating as the changes seen all those years ago.”

So back to offshore wind farms. Most commercial interest outside of our immediate coastline is in the area once Doggerland, with the shallowest water – on today’s Dogger Bank – the prime location. Dogger Bank was the last part of Doggerland to succumb to rising sea levels – around 5000 BCE and thus likely to be the key area for more underwater archaeology.

Vince Gaffney, a landscape archaeologist at the University of Bradford who has undertaken a long term study of Doggerland is worried; In a recent Guardian article he said we still need to know more about the transition from hunter gatherer to more sedentary farming and fishing based communities:

“Mesolithic remains are few and far between but one major sites, Howick village on the Northumberland coast hint that these communities may have led semi-sedentary lives 10,000 years ago.

“We suspect that life might have been much more civilised than we imagine, and that these people had learned to preserve and store food,”

For Gaffney and colleagues, the rapid development of offshore wind power presents an incredible opportunity – and a concern. He says:

“We’re now in the perfect position to explore these areas and extract sediment cores, but we need the funding to do it fast as the opportunity to pursue such research will effectively disappear over very large areas of the seabed, indeed forever, if action is not taken in advance of windfarm development.”

So will Boris allow our Time Teams to do their research? I’d like to be optimistic. However, at the back of his mind might be the fear that such work might show this ‘plucky little island’ to have once been part of a common European home. Quelle Horreur!

Please follow us on social media, subscribe to our newsletter, and/or support us with a regular donation