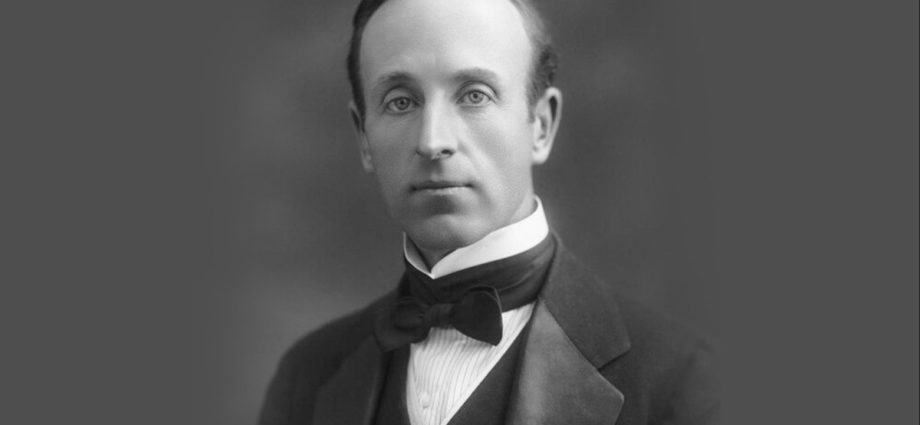

By Bassano Ltd from wikimedia commons

Last week the Middlesbrough Gazette ran a story on the welcome news that a pub in the West Stockton village of Long Newton was to reopen after a protracted closure. But the pubs name led me back to a piece I did for a now defunct blog 16 or 17 years ago, but which, with the UK and other democracies having again to deal with warlike dictators and their oligarchical pals, has fresh resonance. The pub was the Londonderry Arms, a grand establishment in a village owned and laid out in the 1830s by the local landowning Londonderry family when they upped sticks from their native Ulster to marry into the Co Durham Vane coal owning family.

The 7th Lord Londonderry

It was a later 20th century Londonderry that I had mused about – Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, the 7th Lord Londonderry. This Marquess inherited the family wealth and the grand stately home at Wynyard in 1915. Long seated local dislike of the family was intensified in the 1930s when this particular Lord Londonderry assumed high government office in the height of great depression. ‘Charlie’, as he was known to his chums in the languid drawing rooms of the stately homes of England made this worse by becoming a seeming fan of Hitler and of the Nazi regime, and this dislike lingered on long after Charlie’s death in 1947.

Londonderry, as befitted a man of aristocratic breeding and of his mindset as a Durham mine owner, was deeply suspicious of all and any left-wing politics. He believed Britain should befriend Hitler’s Germany to stop communism creeping out of Russia and infecting Europe. To this end, Londonderry visited Germany in December 1935 and February 1936. He went stag-hunting with Hermann Goering (Goering bagged a bison but Londonderry missed everything he aimed at) and stayed for a week at Goering’s luxurious mountain retreat before going on to the Winter Olympics. During his stay, he had a two-hour audience with Hitler, whom he found “forthcoming and agreeable”. Indeed, in a speech in Durham in March 1936, Londonderry described the Fuhrer as, oddly, “a kindly man with a receding chin and an impressive face”.

A visit from Ribbentrop

In return for the hospitality, Londonderry invited German Ambassador Joachim Von Ribbentrop to a later house party in November 1936 at Wynyard Hall. I vividly recall talking to the son of a tenant on Londonderry’s Wynyard Estate who – along with his family – was instructed by the estate to line the road from the now closed Thorpe Thewles Station to greet the Ribbentrop and his entourage with the waving of pre-distributed paper Swastika flags.

But far worse was to come. “The high spot of the autumnal weekend,” says Ian Kershaw in a book on Charlie, ” Making Friends with Hitler: ” “was the grand ceremony of the Mayoral Service at Durham Cathedral.” Crowds thronged the streets hoping to catch a glimpse of Ribbentrop on their way to see Londonderry installed as Durham’s new mayor. The Northern Echo then said what happened:

“The Cathedral organist launched into the hymn ‘Praise the Lord: ye heavens, adore Him’. Alas, this has the same tune as the Deutschlandlied, and hearing this Ribbentrop jumped up from his pew to give the Nazi salute, only for Lord Londonderry to jump on him to tug his hand down”.

It was a scene that could have come out of the closing part of Dr Strangelove.

Even this debacle was not to put Charlie off from touting German government aims as ones that the UK could accede to, almost up to the start of the war in 1939.

So he was a simple bigoted English toff who adored the Nazi regime? Well, actually, it seems, not quite. And this is where Kershaw, in a carefully annotated book studded with copious references, pays us all a service in an act of researched and impeccable revisionism.

The real reason?

For it seems the real reason for his stance was not just anti-communism. It was as much born of pique at the way successive British statesmen had refused to take him seriously as someone destined for high office. His high point as a Tory Peer was as Air Minister for four fleeting years in the early 1930s and then for a few months as Tory Leader of the Lords before being totally dumped by Stanley Baldwin in 1935. He felt with some (and genuine) feeling that he had been used as a convenient scapegoat for the National Government, and put this down to class envy on the part of the emerging army of the ‘new rich’ who had begun to populate the Cabinet Room.

His ostensible fall from grace was due to the fact that as Air Minister, he had vocally and publicly argued for an early re-armament policy based on fast, modern aircraft and defended the offensive use of the RAF as a bombing wing, at a time when most of the left, including the bulk of the Labour opposition who, then led by life long pacifist George Lansbury were in full tonto peacenik mode, and when governing (Tory) politicians of the right wing National Government coalition were totally intent on a cuts programme pure and simple, rather than on any long term policy needs. Hence his fall between two opposing camps and a wide public denunciation across the political spectrum for what he was calling for.

In his aristocratic heart and genes he felt the new generation of self-made men in the cabinet had made an error in dismissing his talents, and were also on the verge of making another huge mistake in confronting Hitler’s Germany whose grievances over the harshness of the Versailles Treaty, were, he felt, justified. In this, ancestral voices played a part, with Charlie echoing his distant forebear Viscount Castlereagh, who, at the Congress of Vienna, argued that he wished to bring back the world to “peaceful habits” after the Napoleonic Wars. As to the people he believed had done him down, all he could say in his diary was that “I now see why I failed to understand the very second class people I had to deal with and how glad they must have been to get me out of the way”.

Charlie was an oaf and a snob, and certainly didn’t deserve better, but it was a supreme irony that it was in his three years at the Air Ministry that he both sanctioned and signed off the development of the first all-metal monoplane fighter aircraft – the Hurricane and the Spitfire. Probably few at the time were aware as they saw the contrails weaving over Kent and Sussex in the autumn of 1940 that the instruments of the RAF’s victory were partly fashioned by someone who felt for Hitler’s supposed kinder side.

If the worst had happened, would Charlie have been among the British collaborationist elite? For what it is worth, I think not. But he would certainly have adapted to life in a Germanised Britain and would have still tried to hope that there was a benevolent side to Nazism which he alone could identify and hopefully draw out.

And – never forget – it was people from his class who later in the century called people like striking Co Durham miners, many of them from families whose forebears had been amongst the Londonderry family’s bonded hirelings, “the enemy within”………………

And his old Wynyard pal Ribbentrop? He was the first arrival on the scaffold to be hanged in the grey dawn of a Nuremberg prison gymnasium block in the October of 1946.

Please follow us on social media, subscribe to our newsletter, and/or support us with a regular donation