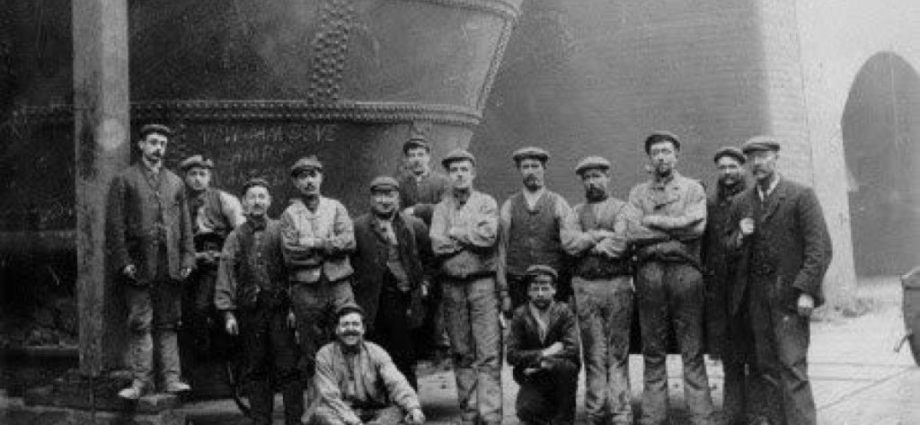

Photo used with permission

The island of Ireland is in the news these days for one reason: the threat of new Brexit restrictions to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. But that’s as far back as we care to go in Irish history. Here is the story of the Teesside turbulence of 150 years ago, when Irish migrants played a key role in the most gripping political drama of the age: the fight for independence in Ireland.

The roots of British rule go back centuries, but a turning point came with the 1798 Irish Rebellion.

At that time, land in Ireland was owned by Protestants and rented out to Catholic tenants who had no voting rights. Ireland was little more than a colony of the Great British Empire which covered a quarter of the world map in imperial pink.

The British government’s response to the rebellion was the Acts of Union of 1800, which imposed full political control but without the promised vote for Catholics which came in 1829.

The town of Middlesbrough did not yet exist, it had 35 souls in the 1811 census. But the region’s entrepreneurs saw ironstone in the hills, the local coal and access to the river and sea. They decided to set up an iron smelting industry.*

A neat town plan on 32 acres was designed, but soon abandoned with the mass influx of workers, handily supplied by Ireland’s Great Hunger.

The Great Hunger

Ireland’s regular famines had taken a new turn. The repeated failures from 1845 of the potato harvest led to a seven-year famine. A third of Ireland relied on potatoes for subsistence The loss of potatoes meant mass starvation.

Many other Irish-grown foodstuffs continued to be exported. The British Government’s handling of the famine was hampered by the economic trend of the time, laissez faire. This small-government policy that left economics to big business and market forces, was the source-DNA of today’s far-right libertarianism.

The Great Hunger looked more like genocide than a natural disaster. A million people died. Two million more left the country, creating emigré populations in the US, Canada, Australia and mainland Britain, including Middlesbrough.

Irish migrants on Teesside

The new Ironopolis had a special attraction for the migrants as the ironworks held no employment bars against Irish or Catholic labourers, unlike the shipbuilding trade. In the latter half of the nineteenth Century, Middlesbrough had the second highest concentration of Irish-born people in Britain after Liverpool.

The famine left a festering wound at home and abroad and the struggle against British rule intensified. There were two strands of resistance: the Constitutionalists or Home Rulers peacefully pressing for Home Rule by an Act of Parliament; and the Republicans, who saw the only solution as seizure of Ireland by force to create a revolutionary republic, and mostly operated in secrecy.

The Fenians

In 1858 the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), or Fenians, was founded in Dublin and New York. They led an insurrection in 1867. With an exhausted Catholic peasant class, it was doomed to failure. But it was enough to spark the sentiments for a republican Ireland throughout the famine diaspora.

Tensions mounted on the British mainland when leaders of the insurrection, plus thousands of the usual suspects, were rounded up. In early 1867 a crowd of up to 30 mn attacked a van in Manchester carrying Fenian prisoners, accidentally killing a policeman. Three men were hanged in November 1867 for the crime of Joint Enterprise.

A few days before the hanging, two more leaders were arrested in London. Two attempts were made to free them from Clerkenwell Gaol. The first bomb didn’t explode, the second misfired, hitting nearby dwellings and killing 12 innocents and injuring 120 more. One man, Michael Barrett, was hanged for their murder in England’s last public hanging.

The Clerkenwell Outrage sent shockwaves through Britain, horrifying those who would have been natural allies of Irish nationalism. It led to more rough justice from the British authorities and an escalation of Fenian violence.

Father Burns

Opposition to Irish nationalism came from an unexpected quarter, the Catholic Church. In 1870 Pope Pius IX issued a decree excommunicating all in the “American or Irish society called Fenian”. The pope had no more zealous champion than Father Burns, priest of the Middlesbrough mission.

Father Burns engaged in a feud with the local Irish, especially the Fenians and Father Bourke, who tended his Irish flock at nearby Port Clarence.

Father Burns pointed out suspected Fenians in his Sunday Mass congregation. One such was John Walsh, a Middlesbrough ironworker, later the North of England Representative on the IRB’s Supreme Council. He is remembered as one of The Invincibles who assassinated the Chief Secretary for Ireland Lord Cavendish in 1882 in Phoenix Park, Dublin. Although evidence connecting Walsh to the fatal stabbings was tenuous, he fled anyway, first to France and then to the US.

Father Burns’ one-man crusade included refusing communion to suspected Fenians, fighting over funding new schools and a torrent of complaints to the Bishop.

Irish Literary Association

Another target for the embattled priest was the Irish Literary Association which began life in December 1870 as the Middlesbrough Catholic Association. Its founders included William Hopson, James McNamee, John Walsh and his brother Patrick. Its immediate aims were setting up a library and the education of poor Irish children. Yet the Association’s events had a nationalist flavour. John Martin, the first Irish Home Rule MP, was met with crowds at Middlesbrough station and two bands played outside the Town Hall before he began his speech. There were also calls for an amnesty of all Fenian prisoners.

Father Burns warned the wealthier townsfolk to steer clear of the Association in the hope of starving it of funds. In a letter to Bishop Cornthwaite he complained:

“They will deny to your face they are Fenians…and the next day they are seen attending Fenian meetings…boasting of their Fenianism and defying all the world” **

Growing tensions

The Irish faced animosity from English workers afraid that they would take their jobs and undercut their wages. There was also a fear of being associated with the Fenians’ acts of violence that had led to the imprisonment of thousands.

Even the First International, established by Karl Marx and the forerunner of the Communist Party, was wary of Irish nationalists.

The Secretary of the First International General Council wrote to the Middlesbrough branch in 1872 enquiring about its aims for a free Ireland in its founding charter, which he saw was contrary to the organisation’s internationalism. The Middlesbrough group, based at the Bolckow and Vaughan Ironworks, replied that it was none of his business.

The irate Secretary reported to the General Council in May 1872. The Middlesbrough group won support from Friedrich Engels, the co-author with Karl Marx of the Communist Manifesto. Citizen Engels argued that the relationship between Ireland and Britain was like the servitude of Poland by Russia.

Teesside reached boiling point in late 1872. A peaceful demonstration in Bishop Auckland in the November, calling for the freeing of Fenian prisoners, drew 10,000 marchers from across Durham.

Six days later in Spennymoor, with three accomplices, Irishman Hugh Slane kicked Englishman Joseph Waine to death. Waine had refused to attend the Bishop Auckland rally.

No defence witnesses

The trial on 17 December would have been cause for an unsafe conviction. The barrister did not meet the defendants as they couldn’t afford him, and no defence witnesses were called.

All four were sentenced to death, but the executions of two who were teenagers, were commuted to life in penal servitude. The other man to hang, John Hayes of Stockton, pleaded his innocence to the scaffold. But at Hayes’ Stockton house a cache of weapons – pistol, swords and pikestaffs- was found.

The coming days saw random acts of violence and in this febrile atmosphere the Stockton Amnesty Riot took place.

On that wintry Sunday the 16 December, up to 8,000 Fenians from Sunderland, Hartlepool, Bishop Auckland, Darlington, Port Clarence and Middlesbrough converged with their Stockton comrades to march to Stockton in protest at the imprisonment of Fenians. They were led by a fife and drum band and flags and banners waved in the cold rain. As they listened to speakers at the Market Cross, a crowd of Englishmen gathered and the inevitable free for all ensued.

There were numerous casualties but no-one died. The organisers received three months’ hard labour apiece.

The Stockton Amnesty Riot marked the end of the Teesside violence but the struggle for Irish independence continued. According to an IRB conference in July 1874, the Fenian movement had 4,000 members across the North accounting for 70 per cent of its members in Britain.

A new priest

Father Burns was replaced in 1872 by Father Lacy, an Irishman and Home Ruler but no Fenian. He restored Middlesbrough’s Catholic Association in 1873 after the Irish Literary Association had wound up.

The new priest soon clashed with John Walsh and other nationalists in 1873 over a newly-founded branch of the Home Rule Association in the town and as a result two rival groups were formed.

Potato blight and Irish Land Wars

In Ireland, a return of the potato blight threatened the 1878 harvest. It sparked the foundation of the Land League to transfer land ownership to tenants and led to the Irish Land Wars. The British government’s response: suspension of habeas corpus and trial by jury, and imprisonment without trial.

There was a Land League branch at Port Clarence, and Stockton had its own Ladies’ Land League group.

Parnell

In these later years the Fenians were eclipsed by the Home Rule movement. Charles Stewart Parnell MP was Leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party which held the balance of power in the House of Commons, keeping Gladstone and his Liberals in office.

But Parnell’s support collapsed abruptly in 1891 with the revelation in her divorce case of his long relationship with Katherine O’Shea. Parnell faced the rage of Liberal nonconformists and the Irish Catholic Bishops. The nationalist movement split between Parnellists and anti-Parnellists. Parnell died that same year from pneumonia contracted during a gruelling election campaign.

Amnesty Association

In May 1891 a Middlesbrough branch of the Amnesty Association was formed after a public meeting, aiming to press for the freedom of Irish nationalist prisoners. Among the touring speakers they hosted was Maud Gonne.

Throughout the 20th century the conflict raged on, a deadly cycle of bloodshed and suppression, until the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

So when there’s horror at the Brexit tinkering with the borders of Northern Ireland, is it any wonder?

* “Middlesbrough as It Was” Norman Moorsom.

** For a detailed account of Father Burns, “The Middlesbrough Troubles of 1871”, Rev Dominique Minskip, in Northern Catholic History, No.38. 1997.

Please follow us on social media, subscribe to our newsletter, and/or support us with a regular donation