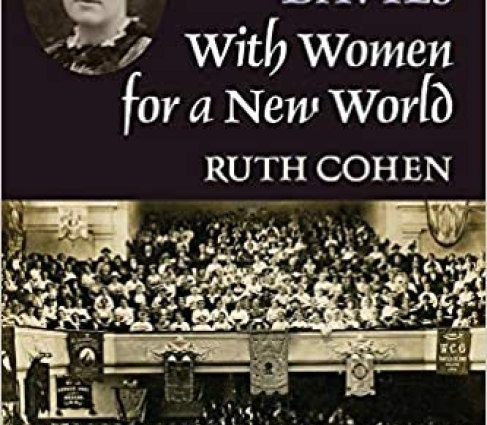

Ruth Cohen’s biography of Margaret Llewelyn Davies (1861-1944) provides a warmly appreciative description of the life, politics, and activism of this outstanding woman. It also brings alive her genius, tenacity, and persistent abilities as a socialist, feminist, and leading activist within the Cooperative Movement.

By all accounts, as Cohen records, Margaret Llewelyn Davies was good looking, charming, and very sociable. She was the second child and only girl of seven talented children in a large upper middle class Christian Socialist family that was part of the influential liberal, literary, and radical intelligentsia of the day committed to the principles of cooperation, and its ideals of mutual aid.

Llewelyn Davies did not marry, and Cohen shows her to have been a loving and conscientious daughter, staying at home until her father died, and dropping everything when needed as sister and aunt during illnesses and the untimely deaths of her brothers.

Girton College for Women

Unusually for a woman at this time, Llewelyn Davies had a university education at Girton College for Women, Cambridge. This indicated the influence of her aunt, Emily Davies, a pioneer of middle-class women’s education and a founder of the College. She did not complete her degree because of the demands on her at home, but Girton introduced her to the idea of a community successfully run for and by women.

Most importantly too, she made lifelong close friends there who would ‘nurture and sustain her throughout her life’. Cohen notes but does not speculate on Llewelyn Davies’s close relationships with women, particularly Lillian Harris, her friend and co-worker in the Women’s Cooperative Guild with whom, on her father’s death, she shared her life and home for the rest of her life.

New World as a Co-operative Commonwealth

Motivated by the belief that a different world was possible through the creation of a ‘Co-operative Commonwealth’, in 1886 Llewelyn Davies joined the Cooperative Women’s Guild founded three years earlier. According to Cohen, the members were from the ‘respectable’ better off sections of the working class who distinguished themselves from those labelled as ‘the poor’. Some worked, but in the main, they were housewives and mothers.

As the General Secretary from 1889 to 1921, Llewelyn Davies championed the campaigns of the Guild for a minimum wage for women cooperative employees; and more broadly, equal divorce rights for women; improved maternity care and benefits; and women’s political suffrage. She also forged a connection between the Cooperative Movement and Trade Unionism which she saw as ‘two halves of the same circle’, through which women workers would develop a sense of solidarity and power to change their lives.

She built up the Guild membership and made it a politically influential organization within and beyond the Cooperative Movement. In 1914 the Manchester Guardian called it “perhaps the most remarkable women’s organisation in the World”. Recognition of her achievements was also obvious in the positive responses and friendship of prominent activists and writers.

Margaret Llewelyn-Davies: changing the world for women

As the Biography’s title suggests, Llewelyn Davies was set on making the world anew through co-operation and collective action. Her aim overall was to bring about political change that improved the lives of working-class women in England, but she was also believed in the importance of international Co-operation. The Russian Revolutionary, Alexandra Kollontai, when visiting a Guild Conference in 1913, was impressed by the radical socialist positions of the women on the pressing class issues of the day. This she said gave the lie to the idea that only factory women could be politicised.

Like all good biographies, this one inspires the reader to look further into the topics covered in the story of the subject’s life that fascinates them. What will solicit many people to keep talking about the book and its subject, however, is the way Cohen brings to life Margaret Llewelyn Davies’ strength of purpose and determination in the face of widespread opposition, within and outside the Cooperative Movement, to give a voice to working class women and their right to “play a part in the Movement and in the wider public world”.

Publishing the ‘voices’ of working women

Llewelyn Davies was, as Cohen says, ahead of her time in seeing ‘life-writing’ by the Guild women as an important component of this influence and how they could tell their stories in their own words. She edited their personal testimonies in two first-hand records of their lives, experiences, and aspirations: ‘No-one but a Woman Knows’ (1915) and ‘Life as We have known it’ (1931). Both provoked a sensation when published.

While sympathetic and respectful of such achievements, Cohen does not avoid contentious issues associated with her subject. She welcomes the critical insights of prior academic and feminist researchers such as Blaszak (2000), Scott (1989), and Black (1989). But she challenges negative assessments of Llewelyn Davies’s leadership qualities and class collaboration with working class women (Blaszak 2000).

The stage for much of this criticism is set by Virginia Woolf’s uncertainties about Llewelyn Davies’s leadership and her observation in her introductory letter to ‘Life as We Have known It’ that, “the barrier is impassable’ between the classes. There is, however, support for Cohen’s position in that, as Woolf worked closely with the Guild locally, Woolf was moved to a greater understanding of them and appreciation of what Llewelyn Davies achieved through her longstanding rapport which crossed class boundaries.

In this first full-scale biography of Llewelyn Davies, Ruth Cohen manages to organize all these complexities and complications of her life into a coherent and readable account. She is to be congratulated for restoring this remarkable woman to her rightful place in twenty-first century Cooperative and Labour history and for showing the continued relevance of her activism to contemporary socialist feminist theory and practice.

More by Ann Schofield

Please follow us on social media, subscribe to our newsletter, and/or support us with a regular donation