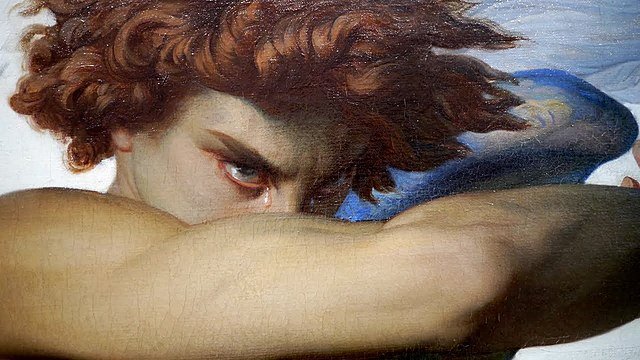

Plays such fantastic tricks before the high heaven

As make angels weep.“

I was reading through the essays of Aldous Huxley recently, creator of our notion of a ‘brave new world’, when I was struck by a piece entitled ‘On a Sentence from Shakespeare.’ Allow me to share the opening paragraph,

“If you say absolutely everything, it all tends to cancel out into nothing. Which is why no explicit philosophy can be dug out of Shakespeare. But as a metaphysic-by-implication, as a system of beauty-truth, constituted by the poetical relationships of scenes and lines, and inhering, so to speak, in the blank spaces between even such words as “told by an idiot, signifying nothing,” the plays are the equivalent of a great theological Summa.”

Phrased like this, one can understand why there is still ‘debate’ over whether Shakespeare was the only author, or even the author at all. And I would certainly recommend Jonathan Bate’s The Genius of Shakespeare for a full appreciation of the lunacy of such arguments. (Arguments promulgated, poetically, by the Edwardian schoolmaster J. Thomas Loony.) But the opening line, that of everything and nothing, is what arrested me. The manifestation of this contradiction is alive in the social media to which we offer ourselves, and the age of universal connectivity we occupy. But there is no genius to marry the relationships between scenes and lines; “told by an idiot, signifying nothing” is exactly what it is. And could easily be the motto of any social media site.

There is something idiotic about those who offer progress as inevitable and undeniably good. Progress in what? How? To what end? Nuclear fission was undoubtedly progress in the field of scientific understanding. If progress means mutual annihilation and nuclear holocaust, or a descent into unthinking Utopianism, then carry on ahead.

The marriage of technological and human progress was ordained by the advertising companies. ‘Our nature and the world are such that, if we make happiness our goal, we shall not achieve happiness,’ wrote Huxley in his “Reflections on Progress”, ‘…happiness, the advertisers teach us, is to be pursued as an end in itself; and there is no happiness except that which comes from without, as a result of acquiring one of the products of advancing technology.’ This once prophetic statement could now be taken for a truism. And the reach of the marketing companies extends beyond consumer goods, or rather, it diversifies the tag of consumer goods, such that the politicians are now manufactured and marketed to the conditioned audience. The Obama campaign of 2008, for example, won two awards at the Cannes Lions International Advertising Awards.

But in his analysis of a sentence on Shakespeare, Huxley is obsessed by those ‘two and a half lines in which Hotspur casually summarizes a whole epistemology, a whole ethic, a whole theology’,

“But thought’s the slave of life, and life’s time’s fool And time that takes survey of all the world Must have a stop.”

Three clauses, of which humanity pays attention only to the first. Thought’s enslavement to life is one of our species’ favourite themes; Huxley points to Adler and Freud, and the Dialectical Materialists, who all “tootle their variations upon it,” but even now we find advertising companies and various sages who, in return for uncritical and unending support, offer up a world of idiotic bliss, of unthinking happiness. There is a modern, secular desire for a father figure, a saint, who will guide us through those slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, and tell us how to live, how to think. We are steadily descending into a society of jellyfish, aimlessly floating through the world, simply reacting to stimuli, rather than thinking things for ourselves.

I was particularly revolted to find in the comments section of a ‘Father’s Day’ post for the ‘intellectual’ Jordan Peterson hundreds of people wishing the man, this stranger, in the most unctuous and vomit-producing tones, a ‘Happy Father’s Day’, or some such variation. Talk about arrested development. Leader worship is one of the most repugnant qualities of our species, especially when the tones take on a quality of fatherly love and devotion.

Now, this is all true so far as it goes; quite false if it goes no further. The very fact that such generalisations can be made, or the fact that there are those saints out there to lead in the first place, is proof that they cannot be true, or required. Yes, thought’s the slave of life; but if it weren’t also something else I would not be writing this piece, and Huxley would never have written a word.

Time must have a stop

Huxley fused his ideas with story in his 1944 work Time Must Have a Stop. It is, in essence, his Summa – of his views on human progress and individual freedom, measured by the value of political creeds as alternatives to true spiritual enlightenment.

The story follows the life of the young martyr, Sebastian, who bears uncommon beauty and a mastery over verse, which contrast sharply with an immature petulance and childish self-indulgence. The desire to be respected as a man of learning, as an ageless talent, despite his appearance and manner is central to Sebastian’s character. The book begins with his rebirth, the reanimation of Saint Sebastian. The unctuous and feeble Mrs. Ockham sees the image of her dead boy in Sebastian, and accosts him after his session in the library:

“His eyes hardened. This sort of thing had happened before. She was treating him as though he were one of those delicious babies one pats the head of in perambulators. He’d teach the old bitch! But as usual he lacked the necessary courage and presence of mind. In the end he just feebly smiled”.

The real world and the world of perception

This split between the real world and the world Sebastian perceives, or desires, is the central theme of the novel. The story takes our childish martyr from the monastic life under his successful and wealthy socialist father to the unreal and exuberant world of Italy and his hedonistic (and nihilistic) uncle-in-law, Eustace. A man of pure indulgence (self as much as material), entirely opposed to the “bullying fool” that is his brother-in-law, but deeply fond of his nephew – “quite a remarkable little creature. Seventeen and childish at that; but writes the most surprising verses – full of talent.”

Under the flabby wing of his uncle, Sebastian experiences the world of luxury his father has starved him of. But despite his best intentions to convince himself otherwise, his acquiescence into this new world does not come as naturally as he would like. It is too much. Upon tasting Roederer 1916 champagne, Sebastian thinks to himself that “it had the taste of apple peeled with a steel knife.” Indulgence requires no thought. And Sebastian is a pensive creature contained almost entirely within himself; price and quality alone are not sufficient to the independent mind. And the champagne represents neatly the position in which he finds himself: between the cold steel of his father’s abstinence and the sickening sweets of his uncle’s perpetual nectars.

Nothing-but philosophies

Huxley takes those ‘nothing-but philosophies’ which he dismisses in his essay on Shakespeare and characterises them in this novel. The socialists (the dialectical materialists) and the hedonists, but also the spiritualists and the aristocrats. The journey of our martyr brings him into contact with each caricature, and each is brought down with a delicious irony; the death of the hedonist from a cardiac arrest, or the ridiculing of the spurious nature of spiritualism in the comical séance scenes. The childish Sebastian acts as our malleable character, our weak and childish faculties of mind, which is guided so easily by the forces of manipulation and coercion to form.

The plot of the story is fairly mundane, and acts only to provide the scaffolding on which Huxley can play the ideologies against fate. As Huxley writes in his essay, “Hotspur’s summary has a final clause: time must have a stop. And not only must, as a prophecy or an ethical imperative, but also does have a stop… it is only by taking the fact of eternity into account that we can deliver thought from its slavery to life.” The death of his uncle forces a change both within him and without. The voice of reason is provided by Bruno, an ageing man of faith, to whom Sebastian is introduced by his uncle, and who immediately sees the prospect of salvation in our saint: “’So this is Sebastian,’ said Bruno slowly. Ominously significant, it was the name of fate’s predestined target.” The old anti-fascist represents the collective views of Huxley. In his religious and introspective character we find an alternative to the Utopian ideologies that claim to have all the answers in exchange only for your critical faculties.

The slave of his thoughts

The epilogue of the novel finds the boy a true martyr. Not quite tied to a tree and shot with arrows Sebastian has lost a hand in combat during the second world war, and sees out his time writing a comparative study of the world’s religions. His life is now the slave of his thoughts. And the war has made the fact of time’s terminal nature all the more available. For that is what this novel is all about. War. The meaningless of it all. And the inevitable end to all the ‘nothing-but philosophies’ which allow to room for dissent, or debate, or criticism.

And the message inherent in this novel and the formative essays is as relevant as today as ever. For while Huxley phrases this in terms of the mystic – Brahman, the Ground, the Clear Light of the Void, the Kingdom of God – which defeats the purpose as far as I can see, and adds unreadable sections to his essays and this novel, the central idea is the same. Think for yourself. Engage in learning and discussion, in argument for its own sake; for thought is not the slave of life, but time does make fools of us all in the end.

The book is best read in tandem with Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy, for which Sebastian’s writings form the basis, and the earlier essays of Huxley contained within The Divine Within. In this age of social media and the subsequent degradation of logic and reason, and of intelligent discourse in politics, Sebastian is epitomised by the multitude who wish to remain young and childish yet demand respect for their views; who are not willing to suffer to obtain true knowledge, or master the ability to think for themselves; those who reduce the world to nothing-but philosophies, in two-hundred characters, or a ten minute video.

“Or,” as Huxley finishes his essay on a line from Shakespeare, “to put the matter in Shakespearean language, if we cease to be ‘most ignorant’ of what we are ‘most assured, our glassy essence…’ then we shall be other than that dreadful caricature of humanity who,

"like an angry ape, Plays such fantastic tricks before the high heaven As make angels weep."

Please follow us on social media, subscribe to our newsletter or support us by donating.